2004%20ink%20on%20paper%20687x.jpg)

2004%20ink%20on%20paper%20687x.jpg)

| Immobilie (Real Estate) |

In this panel, which is almost seven meters high, the spectator is confronted with what looks from afar like the tall, flimsy, bending skeleton of a tower. Here, Ziervogel's typically tortured and torturing, interpenetrating and exploding figures are interlocked along something like a soon-to-collapse scaffolding. The male figures possess the super-hero masculinity of comic books, but despite the vitality of their sadism, none will survive. The ironic title contributes to the depiction of a disintegrating society where stability is a fantasy. It is this society that concerns the artist, not individual depravity. The viewer, trapped looking up at the panel as she might be at any building site, can only see the details at eye level. Above, the hazy intertwined violence continues, and the human chains seem to form odd, light shapes, such as a ball and a balloon, entirely disengaged from gravity. |

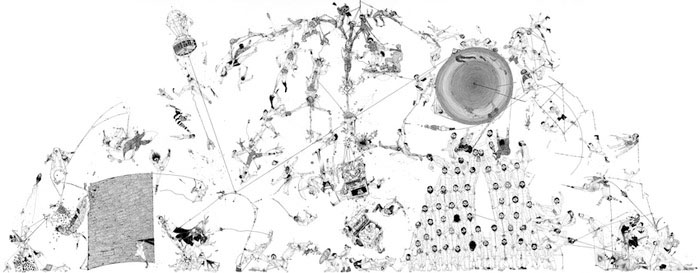

| Heimat |

|

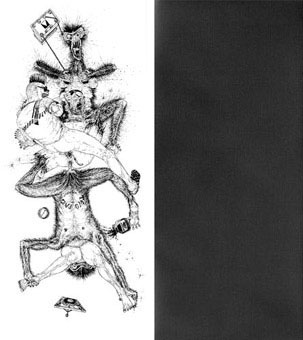

(Every Adidas Got its Story) This small drawing, like the other drawings in the installation called The Fate of the Individual, appears next to the elongated black envelopes often sent in Europe as funeral invitations. The central figure of the drawing, which is entwined with a child, boasts an erection and a bloodied aura. The positioning of the vividly violent drawings alongside their black envelopes suggests a miniature diptych. With this in mind, the figures can be read as a twisted pieta. Around these two, ten smaller figures are roped together in a circle. Ziervogel's drawings invert the familiar Christian motifs, focusing on humanity's brutal suffering rather than that of Jesus. But the piece is equally conducive to a political reading. From this perspective, we may notice that the circling figures look Asian, and that the central figure could well be the monster of globalized economics. Here the work's secondary title comes into (fore) play, both as a specific reference to the Adidas company, and a general economic statement. |