%201989%20Monument.jpg)

%201990%20Selfportait%20with%20Palace.jpg)

%202007%20SplendourMyself-5.jpg)

%202006%20Ambassadors%20of%20the%20Past.jpg)

%201989%20Monument.jpg)

%201990%20Selfportait%20with%20Palace.jpg)

%202007%20SplendourMyself-5.jpg)

%202006%20Ambassadors%20of%20the%20Past.jpg)

Zofia Kulik was born in Poland in 1947, and has been an active and politically motivated artist for some 40 years. In 1968, when Polish students took to the streets to protest a corrupt Communist government, Kulik joined up with fellow artist Przemyslaw Kwiek to make ground-breaking art that addressed cultural repressions. Under the name KK, the two used film, visual documentaries, mail art, the art of action and intervention, performance, and installation. Their work was often made and exhibited in their apartment, which was also their studio, and where they collected an impressive archive. In the 1970s, they were linked to the Soc Art Movement, which was also known as socialist conceptualism, the second socialist realism or New Red Art.

Since 1989, when Poland underwent changes in regime and KK ceased to collaborate, Kulik has been working alone. She developed her own unique multiple-exposure photographic process, which allows her to achieve complex collage effects within a single photograph. Kulik uses historical and other material from her immense archive, which includes serial architectural, militaristic and nude images, and arranges them consistently and decoratively in her photographs. She has shown her work around the globe, and in 1997 represented Poland in the Venice Biennale.| The Monument without Passports |

|

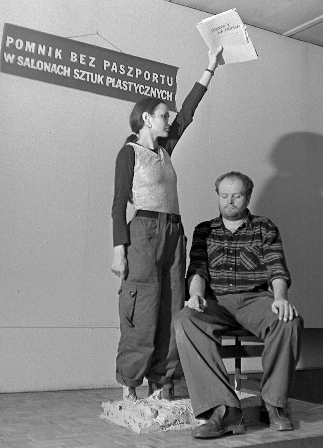

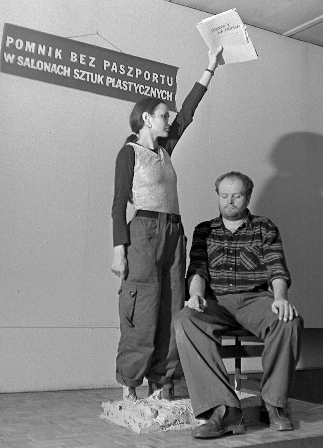

In this performance, the two artists turned themselves into a living monument. It began with Kulik, her head through the middle of a table, reading a letter (in English) sent to organizers at the Arnhem Festival in Holland explaining why KK would not be performing there. The table around Kulik's head was in fact a small screen on which slides were projected. By the end of the performance, Kweik was sitting on a chair which was plastered to the floor, and Kulik was standing by his side in the pose of the Statue of Liberty with her feet encased in a clay pedestal. Instead of a torch, she held documents. Behind them an inscription of the title appeared: The Monument without Passports in Fine Arts Salons. |

| The Splendour of Myself V (Mother, Daughter, Partner) |

|

The frock's fabric is composed of many sets of sequential photographs from Kulik's personal and historical archive, including a male nude in subtly varying positions, skulls, bullets and more. These are arranged into a repetitive, decorative tapestry which evokes coercive force, totalitarian organization and absolute empire. Just under the queenly right hand, a small portrait of Kulik winks at the viewer. The smaller figure holds two others: Kulik's mother, and her partner (Kweik), sitting in the thinking man's despairing pose. In her left hand, the large figure holds a sickle with its many iconic associations, from the harvesting of grains to Communism. Above the figure, a cross (on the left) and a dead bird, add further iconographic weight. The cross is decorated by Eadweard Muybridge-like photographs of men in various stop-motion poses. On closer examination, each of these men appears to be crucified as well. Kulik's use of cut-out patterns for multiple exposures accentuates the fragility and temporariness of the images, and brings attention to the very thin line between visibility and disappearance. |