Stephanie Prussin’s visit allowed her to examine the movement and effect of light in a different geographic, historic and cultural setting. She dedicated her residency to photographing the motion of light in built and open spaces; in particular, she investigated the role of light in places where ritual is observed. She said, “light falls so directly here, there is no mediation.” She added she noticed “that the light in Israel has no gradations. It is less tonal and more extreme (black and white) than in New York.

Prussin visited and photographed Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and went to several museums and gallery shows. She met photographer and curator Noa Ben Shalom for a riveting talk on photography, and had guided tours of the Old City and the archeological City of David in Jerusalem, as well as a tour of Israel’s various borders.

Her invitation to the JCVA residency was made possible thanks to cooperation with Artis - Contemporary Israeli Art Fund and Columbia University, New York.

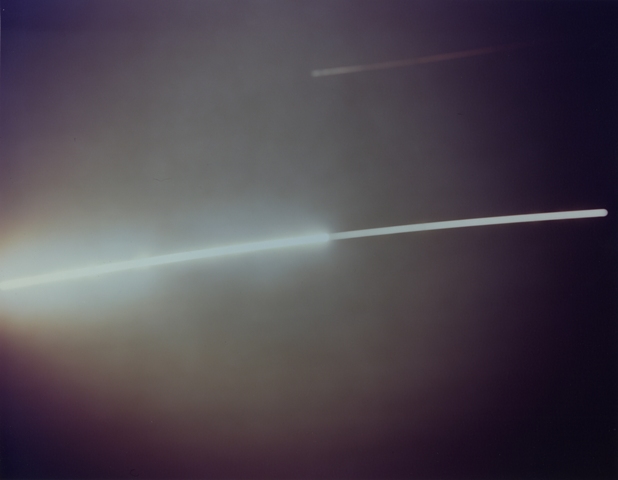

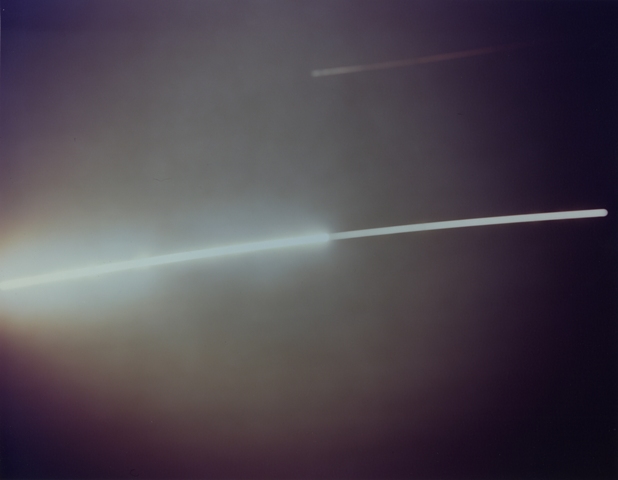

Transmission Reflection (7:05-00:15) and Transmission Reception (9:35-9:40), analog chromogenic color print, 20x24 inch, 2011

The two photographs are part of a series of twelve color prints of analog photographs made in 2011. There are two kinds of photographs in the series – direct photographs of the sun, and indirect photos of sunlight on a wall. They are linked, and were exhibited together at Columbia University.

The series of direct photographs of the sun was taken from a rooftop. The selected photo from the series is a long-term exposure of 17 hours and ten minutes. The second series, also taken with an open aperture, captures the movement of light falling on a wall in Prussin’s room. In the photo selected from this series the aperture was left open for just five minutes.

The work process is experimental. The camera is directed at the focal point, and then -- click. From that point on, there is no control of the photographic product. The particular point in time selected – the day in the year, the hour in the day – as well as the sunlight, shadow and temperature, have effects that cannot be predicted, and the singular result cannot be replicated. The decision when to end the photograph is arbitrary.

The effect and meaning of duration is inseparable from the resulting photographic products. The stretching of time allows the film to accumulate both metaphorical and concrete layers of the motion of light over time and in space. Under these circumstances, the desire to document and capture “truth” is problematized. Prussin offers a kind of documentation that is almost entirely objective, and attempts to compress an inconceivable length of time onto photographic paper. The camera faces a concrete object, but our expectation of a figurative image is met by an abstraction into which time and spatiality have coalesced. The longer the photographic duration, the more nebulous and amorphic the layers of information that accrue, and the more abstract the result. It becomes impossible to decipher the original object of the photograph, something Prussin accentuates by choosing to photograph a visual abstraction -- the sun. In this way she makes sure to preserve the abstract quality of time in her finished works.

The investigation of light, motion and time has always preoccupied artists, so that Prussin’s list of influences stretches along the history of art and photography. She cites Eadweard J. Muybridge, William Henry Fox Talbot and James Turrel in particular.