.jpg)

.jpg)

Tamsin van Essen is a British ceramic designer living and working in London. A graduate of Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art, she specializes in conceptual design and has recently been using the medium of ceramics to explore scientific, medical and social themes. With a scientific approach bred from a degree in physics and philosophy, her work pushes the boundaries of the material to create fragile, thought-provoking pieces that question conventional notions of beauty through the disruption of form. Produced via creative interventions into standard industrial and craft production processes, this work sits at the interface between art and design, with one-off collectibles and conversation pieces.

Van Essen's work has been exhibited extensively throughout the world, including at Sotheby’s and the Saatchi Gallery in London, Le Palais des Beaux-Arts Brussels, Design Miami, the Nobel Museum in Stockholm and other prestigious venues. The work is also on display in the permanent collections of several international museums, including the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Wellcome Collection in London and the Fonds National d'Art Contemporain (French National Collection) in ParisTamsin van Essen stayed at the JCVA for an intensive week in February 2013. This was her first visit to Israel, and as it took place during the Purim holiday, she experienced the playfulness that accompanies the masquerade. In Jerusalem, van Essen visited the Israel Museum and the Shrine of the Book as well as the Old City and East Jerusalem. She was impressed by the dual temporalities that coexist in the city – traditional and historical time side by side with contemporary daily life. In Tel Aviv she visited the permanent exhibition in the Eretz Israel Museum in Ramat Aviv, which is dedicated to ceramics, as well as the Tel Aviv Museum, the Bialik House and the Herzliya Museum. She had an architectural tour of Bauhaus monuments in Tel Aviv and met with architect Meira Kovalsky. van Essen met curator Meira Yagid and representatives of the British Council with whom she explored possible future collaborations. In addition, she toured the Tel Aviv beach promenade and visited Neve Zedek.

In the course of her visit, van Essen spoke about her work at the Design Museum Holon before dozens of designers, artists and students who were eager to hear about her approach to material processes; she also contributed some samples of her singular work to the museum's materials library.

While she was in Israel, her work Ornamental Metamorphosis was shown in the group exhibition Smashing! Fragility, Deconstruction and Fragments in Contemporary [Ceramic] Arts at the Benyamini Contemporary Ceramics Center in Tel Aviv.

Van Essen said that the intensive presentation of her work over her short stay allowed her to observe her creative process retrospectively, but also afforded her some time and space to consider future irections.

Warped Light

2008, Slip cast bone china, Diameter 14 cm.

These lighting fixtures look like Chinese paper lanterns, but are made of highly translucent bone china. Intending to maintain the accordion folds typical of the paper lanterns, van Essen interrupted the normally controlled firing of the pieces so that each was captured at a moment of collapse wherein it received its individualized shape. The result is rigid, mass-made bone china pieces that are nonetheless unique, and emanate lightness and mobility.

Bone china is a ceramic with a high degree of transparency. It was developed in England in the 18th century to compete with Chinese porcelain; the latter had dominated international markets for many years and stood for excellence and durability. In Warped Light, van Essen use of the derived (British) material, as well as of the lantern shapes derived from Chinese tradition, points to the impossibility of making perfect copies, and to the vast array of possibilities that lie in the space between the original and the imitation. This piece can be read as a subtle critique of the standardized products we consume and the uniformity they impose.

The very production process of this design, which the artist fashioned for sale and mass consumption, in fact speaks of uniqueness and the one-off item. The work challenges mass reproduction and its claim to economic efficiency. Here, each object remains an original rather than a copy.

Warped Light was exhibited in 2008 in the Tina B. Prague Contemporary Art Festival. Van Essen hung dozens of the lanterns as lighting installations; they generated a warm, domestic feeling in the cold industrial space.

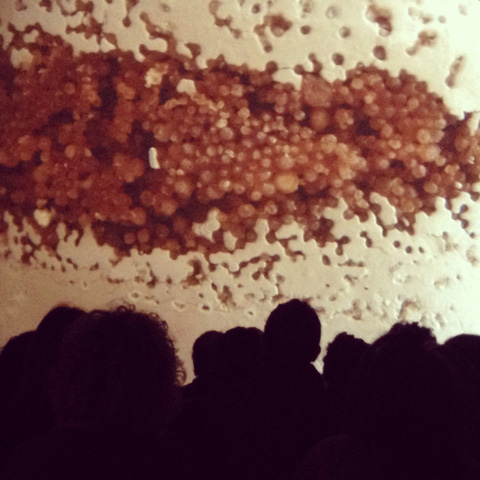

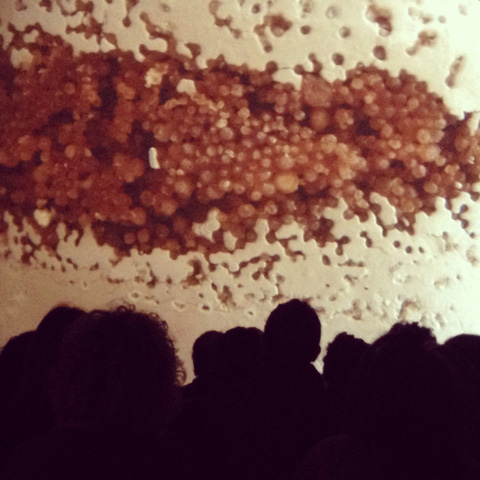

Medical Heirlooms

2007, Ceramic material

With her background in physics, philosophy and ceramic design, Tamsin van Essen uses design and art practices to ask significant questions regarding science, medicine, raw materials and the cultural perception of such materials.

Van Essen uses the archetypal form of the vessel as a means to discuss science and the body. The ceramic pots are shaped like apothecary jars in popular pharmaceutical use in the seventeenth century; such jars are now nostalgic collectors' items, culturally and historically associated with medicines. Van Essen gives these vessels skin (sometimes a second skin, sometimes singular), that speaks of illness. The series includes dozens of ceramic jars that look as though they were struck by visible disease conditions such as osteoporosis, psoriasis, acne, cancer and syphilis. Her objects are simultaneously body and its protective membrane, disease and its remedy.

The realistic sense of decay conveyed by van Essen creates a strong response that swings from a palpable repulsion to attraction to the beauty and delicacy with which the material was handled. The character of the work as an object of desire has been undermined; instead, though it raises the viewer's interest, it is in fact uncanny. As in other works, van Essen challenges our expectations regarding the familiar, domestic object, and questions the relationship of the self to danger.

The project's name is multivalent. It relates to the fact that both precious objects and diseases can be passed down through the generations.

Van Essen further challenges the object's usual standing by placing it in the context of a museum of the history of science in London, beyond the pale of the gallery world. This is yet another transgression, another way of confusing familiar expectations. The work begins with ceramics qua material, but this materiality does not delimit the terrain where it operates; rather, the work moves freely between ceramic design, industrial design, art, psychology and science.